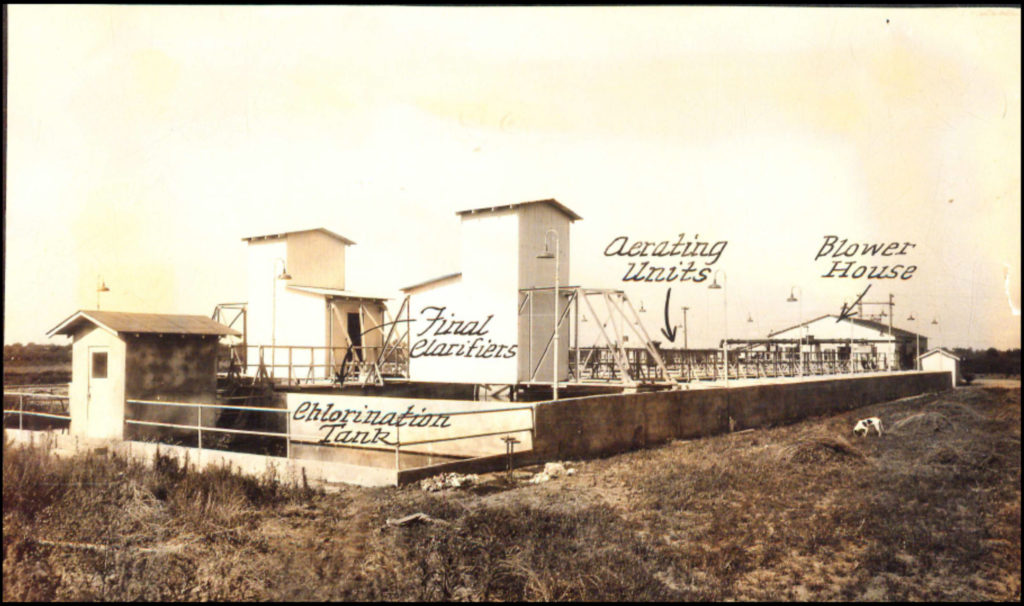

The Original City of Lodi 1923 Sewage Treatment Plant

The Significance City of Lodi’s 1923 Sewage Treatment Plant

The CWEA History Committee published an article in the winter 2017 edition of the CWEA Wastewater Professional documenting the centennial of the use of the activated sludge process in California (1917-2017). As discussed in the article, the adoption of the activated sludge process by California utilities really “took off” in the 1920’s and the early history of the utilization of activated sludge is intertwined with the history of CWEA.

A remarkable fact emerged from the History Committee’s research involving the adoption of the activated sludge process in California; the City of Lodi holds the record for the longest continuous use of the activated sludge process for municipal wastewater treatment in California – 96 years in 2019! Additionally, the CWEA History Committee acquired film footage of the Lodi treatment plant that was taken during the California Sewage Works Association’s (CSWA) April 1930 conference tours.

One of the CWEA History Committee’s activities is documenting California wastewater facilities that are historically significant in terms of the evolution of infrastructure, the evolution of technology, and for our association’s history. Given the City of Lodi’s record for its pioneering use of the activated sludge process, the use of its facilities for CWEA training and conference papers, and the City’s history of supporting the training and development of CWEA leadership, the City of Lodi’s 1923 sewage treatment plant more than meets the History Committee’s criteria for documentation.

The Beginnings of Activated Sludge in California

California’s first activated sludge treatment plant was constructed in 1917 to serve Folsom State Prison, which is noteworthy considering that the activated sludge process was “invented” in 1914. The 1917 Folsom State Prison plant was “largely a design” of the State Department of Health’s Bureau of Sanitary Engineering (Bureau), led at that time by CWEA “Founding Father” Chester Gillespie. The use of activated sludge at Folsom State Prison was driven by the fact that the prison discharged partially treated septic tank effluent into the American River upstream of the Prison’s drinking water intake. Unfortunately, this practice resulted in outbreaks of typhoid fever at Folsom State Prison. The public health issues, plus the limited space for a treatment plant, made the new activated sludge process an attractive alternative to other available treatment processes, and staff with design experience in activated sludge were hired by the Bureau (notably Ralph Hilscher and later Clyde F. Smith).

There was a lag of about four years before the next full-scale activated sludge plant was constructed in California (pilot plants were used to test the activated sludge process in California during the 1916-1921 period). The City of Turlock was the first California municipality to construct an activated sludge treatment plant in 1921. The City of Lodi was next in line and applied for a permit to construct its activated sludge wastewater treatment plant in 1922. While the City of Turlock’s proprietary L.C. Trent treatment plant failed and was replaced by an Imhoff tank treatment plant in 1927, the City of Lodi’s activated sludge plant successfully operated at the South Ham Lane location until 1967 when new treatment facilities were constructed at White Slough (present site of the City of Lodi wastewater treatment plant).

Sewage Treatment in Lodi Prior to 1923

The City of Lodi constructed its municipal sewer system around 1910 and, like many small California cities of the time, used septic tanks followed by a contact bed to treat its wastewater. The contact bed consisted of an uncovered water-tight tank filled with broken stone media to oxidize the septic tank effluent by a “fill and draw” operation. The treated effluent from the contact bed was discharged to a nearby canal owned by the Stockton-Mokelumne Canal Company (now the Woodbridge Irrigation District South Main Canal). Lodi’s septic tank/contact bed treatment plant was located at the present site of the City of Lodi Municipal Services Center at Kettleman Lane and South Ham Lane.

The original City of Lodi treatment process worked, provided that the sludge from the septic tank was periodically removed and the fill and draw schedule for contact bed was adhered to. Unfortunately, according to the Bureau, the system was not properly maintained and by the time the City filed for a permit to construct the activated sludge plant, the septic tank and contact bed had been partly out of service for several years. Raw sewage and poorly clarified septic tank effluent were periodically discharged into the canal.

The lack of proper treatment created several problems for the City of Lodi. First, the irrigation canal was dry approximately six months out of the year (as is typical for irrigation canal systems), thus undiluted sewage would flow several miles down the length of the canal creating nuisance odors and flies. Second, per the Bureau, there were several “exceptionally fine country homes” and other residences near the canal and the effluent discharge point – the owners of these homes complained to the Bureau about the nuisance. Third, the Bureau found that there were several thousand acres of crops being irrigated with sewage from the canal. Finally, the Bureau determined that farm laborers were drinking water from the canal and irrigation ditches from the canal downstream from the City’s effluent discharge. The Bureau described the discharge as “a gross pollution of irrigation water” and insisted that the City act to correct the situation.

Solving the Sewage Problem

The initial proposal to solve Lodi’s problem involved piping the sewage several miles west for disposal in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. This idea was dismissed due to recommendations by the Bureau and the advice of Clyde F. Smith, who was retained by the City as a consultant. Based on Smith’s recommendations, the City selected the activated sludge process as the preferred treatment alternative.

The decision to use activated sludge was based on the desire of the City of Lodi to use the existing septic tank/contact bed site for the new treatment plant. Reusing the site had the advantage of saving the costs of a pipeline to the Delta and saving land acquisition costs for a new treatment plant site. However, reusing the existing treatment site meant that the new treatment plant would need a relatively odor-free treatment process that could produce a high-quality effluent and, at the same time, have a compact plant footprint. The activated sludge process met these criteria and Clyde F. Smith was retained to prepare plans, specifications, and a permit application for the new treatment plant in 1922.

Smith submitted the plans and permit application for the new City of Lodi treatment to the Bureau on December 11, 1922. The Bureau reviewed the application and plans and Director Chester Gillespie responded to the City of Lodi by issuing a “provisional permit” on April 23, 1923, which allowed the City to proceed with the construction of the new treatment plant. One of the major reasons the Bureau granted the City of Lodi a provisional permit was based on concerns regarding the potential for creating a nuisance due to the site’s proximity to residences and the potential for plant screenings and sludge for generating flies and odors. The Bureau staff preferred a site a half mile northwest of the existing plant site, or at least moving the plant 500 feet further north of the existing plant site to create a buffer zone for the homes in the area.

In addition to concerns related to the new plant’s location, the Bureau was also wanted assurances that the City would provide adequate funding to operate the plant and provide skilled operators for the O&M of the facilities. The Bureau also noted that the plant design included a bypass to the irrigation canal, which could perpetuate the contamination of irrigation water, and Bureau staff noted that there were no provisions for disinfecting the plant effluent. The handling of screenings and sludge were “uncertain” according to the Bureau’s review of the plans. This uncertainty, coupled with the Bureau staff’s lack of experience related to the performance of the activated sludge process for treating municipal sewage, reinforced the decision to issue a provisional permit to the City of Lodi.

Based on these concerns, the Bureau issued the following conditions for the one-year provisional permit:

If the bypass prohibition and effluent disinfection conditions were met and the plant successfully operated for one year without creating a nuisance, the Bureau would issue a full permit to the City of Lodi. The City was able to successfully meet the provisional permit conditions and obtain its full permit – the sewage problem was solved!

Overview of Plant Processes and Operation

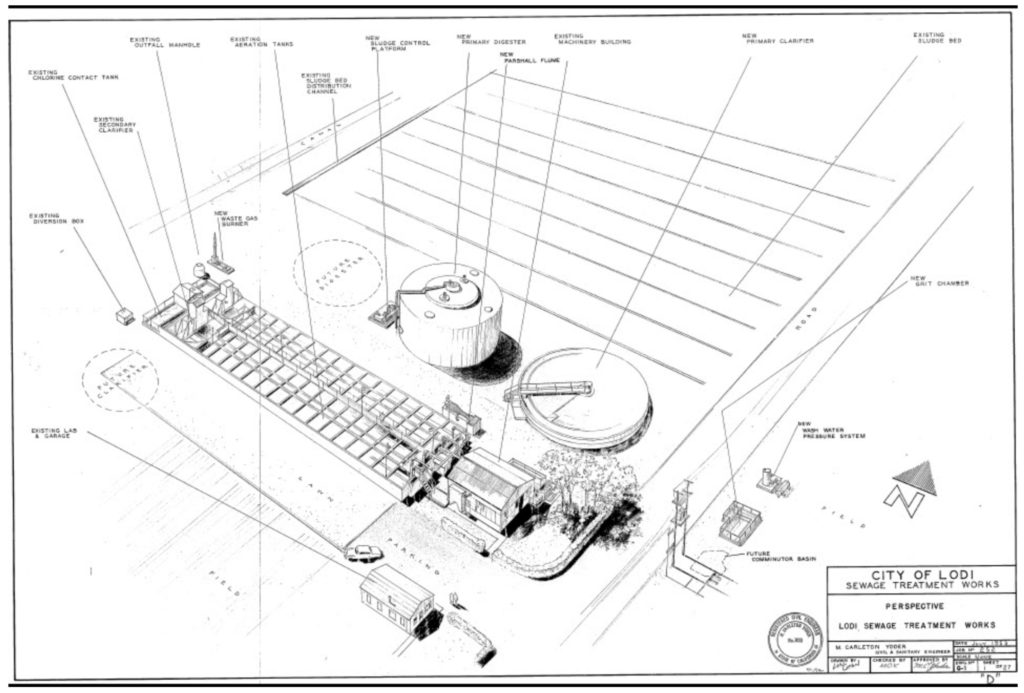

City of Lodi Wastewater Treatment Plant Perspective Showing 1953 Improvements at the Original 1923 Plant Site (source: City of Lodi)

The City of Lodi’s service area population was approximately 4,900 when the new activated sludge sewage treatment plant was placed in service on November 7, 1923. The total construction cost for the new plant was $148,000 in 1923, which is approximately $2,201,000 in 2019 dollars.

According to the 1930 CSWA Annual Conference paper, the Lodi plant served a connected population of approximately 7,500 with an average flow of approximately 0.975 MGD. Per the 1930 conference discussion, Lodi’s flat rate water service contributed to a higher than average sewage discharges per capita than communities with metered water service. The plant was designed to treat domestic wastewater and local cannery wastes were not treated at the facilities. The 1930 conference paper also stated that the City of Lodi had 28 miles of sewers, running generally from east to west, and that the system was segregated from the City’s stormwater collection system. It was also noted that only one City employee was required to maintain the sewer system.

Per the original plant design, plant flows were measured by v-notch weirs and plant influent flows were equalized by using the old 1910 plant’s septic tanks. Raw sewage from the repurposed tanks first passed through a bar screen and then through a 4 foot-diameter by 5-foot Dorrco cylindrical fine screen. The screened effluent then entered a wet well and was lifted by Byron-Jackson pumps into influent channels where it was mixed with return activated sludge prior to entering the aeration tank.

The aeration tank was divided into two parallel units and equipped with diffused aeration via “Filtros” plates, which were the commonly used diffusers of the era. Air was supplied through four Nash “Hytor” air compressors or blowers at the Lodi plant, including three No. 4 and one No. 7. The No. 4 compressors each had a capacity of 450 cu. ft. per min. at 10 lb. pressure, and the No. 7 had a capacity of 1,400 cu. ft. per min. at 10 lb. pressure. Air was supplied to the sewage through pipe lines which connect to the bottom of the aeration channels and was released through the Filtros diffuser plates at a depth of 16 feet.

The reported detention time in the aeration tanks was 4 hours and the aeration rate was 0.6 cubic feet of air per gallon of sewage, which produced very good results with dissolved oxygen averaging 4.3 ppm. The City of Lodi found that the Filtros plates worked well – the original diffuser plates installed in 1923 were in continuous use through 1937 with no reported operation and maintenance issues.

The aerated mixture was discharged to “Dorr” secondary clarifiers from which the effluent passed over a weir to a chlorine contact tank for disinfection. The final effluent was then discharged to the nearby irrigation canal. Return activated sludge was collected in the secondary clarifiers and forced into a sludge return channel where it was reaerated prior to being returned to the influent channels.

Screenings from the plant were buried and the waste activated sludge was dried on open drying beds. Approximately 24 tons of sludge per year were produced during the first decade of operation and the dried sludge was found to be relatively odor-free and stable. Initially, the dried sludge was given to area farmers free of charge. By the mid-1930’s it was reported that Lodi’s dried sludge was sold by lump-sum contract, bagged and shipped to agricultural users south of Lodi.

The City of Lodi’s sewage treatment plant had no reported operational issues. Per the journal articles, the key to operating the plant was monitoring and controlling the amount air used to aerate the mixed liquor. The plant had originally been equipped with meters for measuring air flow, but these were found to be unreliable and the operators used blower run-time until new metering was installed in the 1930’s.

In terms of performance, the Lodi plant’s reported removal of BOD averaged 92 percent, removal of suspended solids was reported as 85 percent, and nitrogen removal was reported at 41 percent.

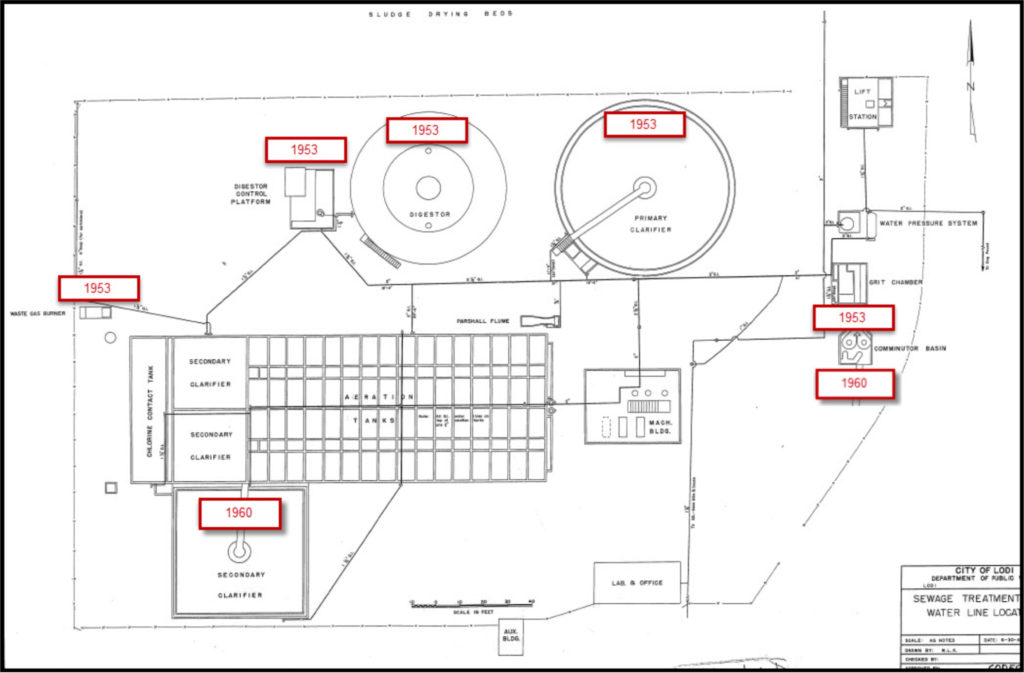

1953-1960 Lodi Plant Improvements

By 1953, the Lodi Sewage treatment plant needed improvements to address population growth and enhance treatment performance. The 1953 design factors show Lodi as having a population of 13,727, with improvements being designed for a target population of 25,000.

The 1953 plant improvements included the addition of a grit chamber, a 76.4-foot diameter primary clarifier, a 70-foot diameter anaerobic digester, a waste gas burner, a Parshall flume for flow measurement, and a pressurized wash water facility. Provisions were made for a future secondary clarifier, a second digester, and a comminutor basin ahead of screening. Plant plans show that the proposed secondary clarifier and comminutor basin were constructed by 1960. This would be the final configuration of the City of Lodi’s sewage treatment plant through 1967 when the sewage treatment facilities for the City were relocated to its present location at White Slough.

Plant Plan showing the Core 1923 Plant Infrastructure, the 1953 Improvements and the 1960 Additions (source: City of Lodi)

The 1923 City of Lodi Sewage Treatment Plant and the California Sewage Works Association (CSWA)

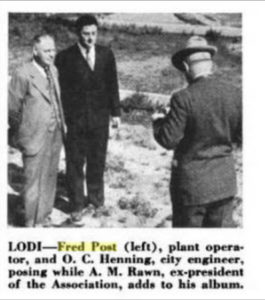

The CSWA recognized the City of Lodi’s sewage treatment plant as the first municipal treatment plant in California to successfully utilize the activated sludge process. This fact is referenced in articles in the CSWA Journal starting in 1929. Also, it is noteworthy that four City of Lodi staff were charter members of the CSWA at its start-up in 1928: Leon F. Barzellotti (City Engineer), J.F. Blakely (City Clerk), John A. Groz (Plant Operator), and Fred W. Post (Plant Manager). The fact that four City staff were charter members of the CSWA is significant considering the size of the City and that the total number of Association members was 115!

Lodi Plant Manager Fred Post and City Engineer O.C. Henning during the 1937 CSWA Conference Tour of the City of Lodi Sewage Treatment Plant

The City of Lodi’s early support for the CSWA was indicative of its future support for training and staff development. Lodi Plant Manager Fred Post would later become the first president of CWEA’s first local section in 1938 (the San Joaquin Section) and various City of Lodi staff continued leadership roles in CSWA Statewide Committees, the San Joaquin Section, and later in the Northern San Joaquin Section. Notably, City Lodi Water/Wastewater Superintendent Fran Forkas served as CWEA President during 1989-90 as part of this trend.

Because of its status as a pioneering activated sludge plant and the fact that it had almost no operational issues, the CSWA selected the City of Lodi sewage treatment plant for the one of the site tours held during its 1930 and 1937 Annual Conferences. The plant was also the site of the CSWA managers’ and operators’ short school during the 1930 Annual Conference, as well as the subject of a conference paper published in 1930. Additionally, the Lodi plant selected for study by Bureau in 1931 and the results were published in CSWA Journal. The Lodi sewage treatment plant was also the subject of CSWA Journal papers and conference presentations in 1932 and 1937. Finally, the City of Lodi was presented a CSWA Award of Merit (equivalent to the CWEA Plant of the Year Award) in 1939.

1930 City of Lodi Sewage Treatment Plant Film

The CWEA History Committee is fortunate to have a short film of the City of Lodi’s sewage treatment plant taken during the 1930 CSWA Annual Conference Tour. The film was taken by CSWA and Federation Past-President A M Rawn who was an amateur cameraman and his films preserve some unique views of California’s wastewater history.

Rawn’s film captured views of the Lodi and plant and the CSWA tour, which are valuable for documenting both the plant and the CSWA event. Based on the film, Rawn was particularly interested in the performance of the activated sludge process and the clarity of the plant effluent. The CWEA History Committee was able to identify CSWA President Fred Batty in the film allowing us to add another photo of President Batty to our archive. Two frames from the film are shown below.

Documenting a Trail Blazer

Film Frame Showing CSWA President Fred Batty (on right) at the City of Lodi Treatment Plant Tour, April 22, 1930

The CWEA History Committee is pleased to be able to document another of California’s historically significant wastewater facilities. The City of Lodi’s 1923 sewage treatment plant was a “trail blazer” for the activated sludge process in California and the City’s long-term use of the process is truly a noteworthy part of our wastewater history.

In keeping with its pioneering history, the City of Lodi continues to operate a state-of-the-art wastewater treatment facility utilizing the activated sludge process and has provided treated effluent for agricultural reuse since the 1940’s. Currently, the City operates a 790-acre agricultural reuse and biosolids application area.

In closing, the CWEA History Committee would like to thank CWEA Past President Fran Forkas and Charles Swimley, City of Lodi Director of Public Works, for their assistance in providing information for this article.