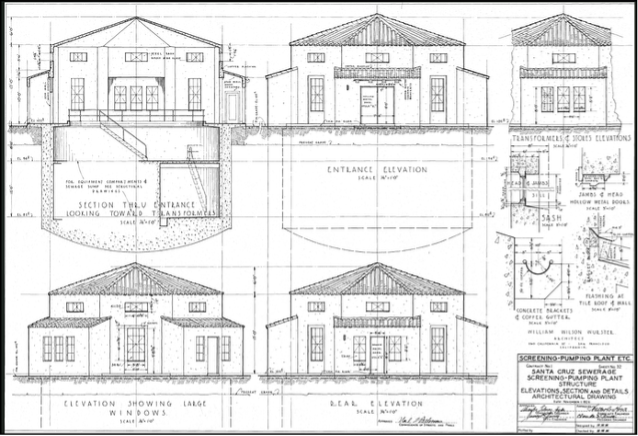

Figure 1. The 1928 City of Santa Cruz Screening and Pumping Plant Elevation and Details (image courtesy of the City of Santa Cruz)

To prepare for the 2028 CWEA Centennial, the History Working Group is investigating important wastewater-related milestones from the year our Association was established. A notable milestone was the City of Santa Cruz completing its inaugural comprehensive wastewater collection system, treatment plant, and ocean outfalls in 1928. Importantly, CWEA founding members Chester Gillespie and Charles Gilman Hyde played key roles in the 1928 Santa Cruz project. Gillespie managed state health requirements and delivered public presentations advocating for enhancements, while Hyde developed master plans and designs for the new facilities.

Santa Cruz began installing sewers in the 1880s in the Mission Hill area, channeling wastewater into Neary’s Lagoon. By 1917, about 75% of the city had sewer systems; the rest relied on vault privies or septic tanks. Apart from the beach, the city’s west side had a sewer system discharging into the Pacific Ocean by gravity, except for the sewage from the business district, which was pumped. The town used septic tanks that discharged into the San Lorenzo River, Branciforte Creek, or Monterey Bay, sending waste to popular bathing beaches via river flow and tides.

On July 18, 1917, the Bureau of Sanitary Engineering, under the direction of Gillespie, prepared a special report for the California State Board of Health (CSBH). A section of the report focused on the mouth of the San Lorenzo River, addressing a series of issues. The most serious concern arose from bathing in the San Lorenzo River, approximately 1,000 feet upstream from the mouth. A large sandbar had formed there, and the water was warmer than that of the bay, making it a popular spot.

A rental bathhouse was available in the area for river bathers. The stream’s natural summer flow was minimal, relying on tidewater to enable this activity. The tidewater also helped carry away sewage from nine septic tanks upstream. Additionally, during the incoming tide, sewage from the East Side sewer at the river’s mouth was pushed back over the bathing area. This posed a serious public health risk, leading to a ban on river bathing.

As a result, on Aug. 15, 1917, the CSBH advised the Santa Cruz City Health Officer to quarantine the San Lorenzo River against bathing for 1,000 feet above its entrance into Monterey Bay until the threat could be removed.

The mouth of the river remained quarantined until 1928, when the city’s new screening plant, interceptor sewers, and outfalls were built. A section of Monterey Bay beach in Santa Cruz was also quarantined for a short time in 1925 by the CSBH due to contamination from a discharge of raw sewage in the area.

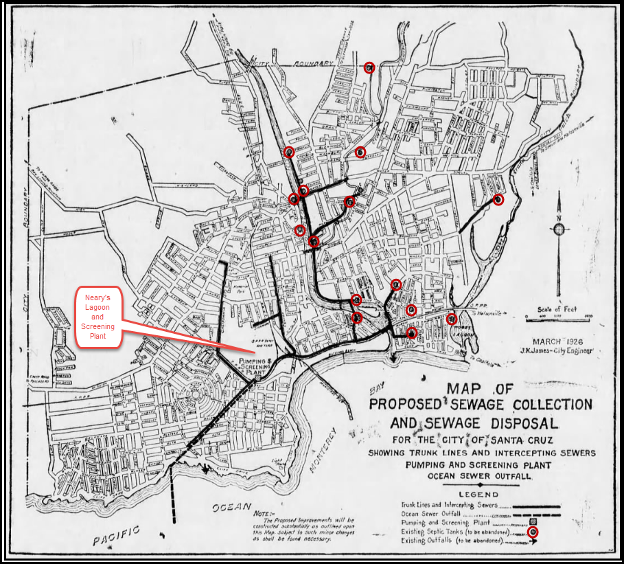

In 1925, the City of Santa Cruz engaged consulting engineers Hyde and Walter C. Howe to conduct a comprehensive study of the city’s sewage collection, treatment, and disposal. Their study led to the completion in 1928 of a recommended network of intercepting and trunk sewers, as well as the abandonment of the municipal septic tanks (see Figure 2).

The consultants’ work showed that treated sewage could be safely discharged into Santa Cruz Harbor through a submarine outfall, proving it the most economical alternative. However, citizens opposed to potential threats to the nearby beaches protested. In response, the City Council opted for a more expensive treatment effluent disposal option, which involved outfall pipelines extending 2,000 feet into the ocean.

In addition to the decision to extend the outfall pipelines, the City also decided to construct a screening plant, as it was believed that this type of treatment would be more economical to operate and create less of an odor problem than the initially proposed activated sludge treatment process.

In 1925, Gillespie reported that 82 percent of U.S. cities with populations over 100,000 disposed of sewage via screening and dilution, notably Los Angeles’ Hyperion Treatment Plant. For coastal cities, screening and ocean disposal were deemed acceptable.

The Santa Cruz screening and pumping plant was completed in 1928 at the current wastewater treatment site. Interceptor sewers were installed to collect sewage from collection systems within Santa Cruz and convey it to the plant.

During planning, engineers identified stormwater infiltrating existing sewer systems. Reports indicate that older sewers, particularly in low-lying areas, and many house connections were poorly constructed, allowing excessive groundwater entry. Some sewers occasionally surcharged as a result. They recommended that a thorough investigation was needed during high groundwater periods to pinpoint severe leaks.

They also recommended that affected sewer sections should be repaired as funding allowed. The interceptors were designed for flows larger than those typically expected for the design period. From the time the interceptor sewers were constructed in 1928 until 1950, several bypasses were installed in the sewer system to allow escape of excess flows. These bypasses were removed after 1950 as system improvements were made.

Figure 2. 1925 Map Showing the Proposed Project Improvements

(Note: 15 septic tanks are shown as scheduled for abandonment as part of the project)

On March 30, 1926, Santa Cruz residents participated in a special election, voting to issue bonds totaling $450,000 to upgrade the sewer system and develop ocean outfall works. The plan encompassed seven major projects and thirteen different propositions, each with associated cost estimates. Two primary disposal methods were proposed: diluting screened sewage effluent in Santa Cruz Harbor and the Pacific Ocean, and treating sewage effluent using the activated sludge process. The preferred alternative was that ‘dilution is the solution for pollution.’

To dispose of the city’s sewage, the Pacific Ocean was chosen over Santa Cruz Harbor. A solitary rock surface with some temporary sand near the shore was identified south of Cliff Drive and Sunset Avenue. Constructing a force main in a tunnel beneath the plateau accessed this area, extending about 4,400 feet from Neary’s Lagoon to the shore. Before the 1927 improvements, 15 small public sewer systems served the area, with 13 discharging into septic tanks and the rest emptying into the San Lorenzo River, Branciforte Creek, and Santa Cruz Harbor.

The 1927-28 improvements consolidated the sewer collection systems into a single system, conveying all sewage to a new screening and pumping plant at Neary’s Lagoon. In 1925, Santa Cruz had an estimated population of 15,000. Using this as the base, projections extended to 1970. The new treatment facility was designed for a population of 40,000 for $420,000.

The project included several components, such as various types and sizes of sewer pipes, including vitrified clay and Portland cement concrete. It also involved crossing rivers, creeks, gulches, and railroads, utilizing copper-bearing steel, hand-puddled wrought iron, and cast-iron pipe. Additionally, they added two 16-inch outfall wrought iron pipelines, each extending 2000 feet into the Pacific Ocean.

A reinforced concrete screening plant with a tile roof was constructed in Neary’s Lagoon. The structure comprised two bar screen channels, a 25,000-gallon sewage sump and wet well, a pump chamber, two rotary screen chambers, a screening pit, an ejector pit, an operating floor, an attendant’s room with a lavatory, a transformer alcove, and a storeroom.

The new plant’s equipment included a 36-inch float control, an automatic emergency backpressure sluice gate, two removable bar screens, and two 6-foot Dorrco rotary fine screens powered by a five-horsepower motor. It also had a Dorrco bucket elevator with a one-horsepower motor and a pneumatic ejector with a 15 cubic feet capacity.

The screening and pumping plant received immediate praise for its attractive Spanish-style architecture (see Figure 1), smooth operations, cleanliness, and lack of odors. The press noted the efficiency of the fully automated equipment and admired the landscaping, including the aquatic gardens with a canal and bridge.

The 1928 Santa Cruz project was successful, staying within budget while improving the environment, public health, and aesthetics. The Santa Cruz Screening and Pumping Plant was included in two Association conference tours, and several papers on its design and operations were presented at California Sewage Works Association (CSWA, now CWEA) conferences.

Note: Special acknowledgement goes to Santa Cruz Public Library and the City of Santa Cruz Public Works Department, Wastewater Treatment Division, for providing documentation and drawings used in this article.