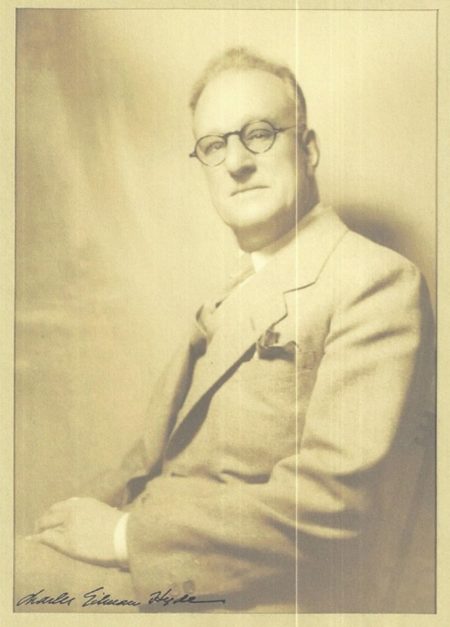

Charles Gilman Hyde was born in Yantic, Connecticut on May 7, 1874. He was the youngest of Rodney and Kate Rhode Hyde’s nine children, five of whom died in one of North America’s last cholera epidemics. It has been speculated that it was this tragedy that drew Professor Hyde to the field of Sanitary Engineering.[1]

Hyde enrolled in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Sanitary Engineering program in 1892 – a program that had been established a mere three years earlier. He distinguished himself at MIT, becoming Class President (1895-96), President of the Institute Committee, President of the N.E. Intercollegiate Press Association (1895-96), Editor (1892-94) then Editor-in-Chief (1894-96) of “The Tech”(1894-96), Associate Editor of “Technique” (1896), Secretary of the MIT Yacht Club (1894-95), Undergraduate Representative at the annual Alumni Dinner (1896), a Class Day Committee Officer, and the presenter of the address at the Class of 1896 Senior Dinner.[2] Based on school publications, Hyde’s fellow students, none of whom came close to his level of energy and activities, saw him as popular and capable leader. These qualities combined with his ability to “multitask” continued throughout his professional career as a highly productive educator, scholar and consulting engineer.

In 1896 Hyde graduated with the B.S. degree in Sanitary Engineering. His senior thesis, titled “Design for a System of Sewerage and of Sewage Disposal for the Town of Needham, Massachusetts” (co-authored with William H. McAlpine), set the stage for his future involvement in numerous wastewater projects.[3]

From 1896 to 1900 Charles Gilman Hyde, “cut his teeth” in the practice of sanitary engineering as an assistant engineer with the Massachusetts State Board of Health, then from 1900 to 1902 as the engineer in charge of testing stations for the City of Philadelphia Bureau of Water.

He further refined his skills in water supply assessment and treatment facility design as the resident engineer for the investigation, design and construction of the Harrisburg Pennsylvania Water Filtration Works (1902-1905).[4]

Hyde’s experience with the Massachusetts State Board of Health was particularly significant to his professional development as a sanitary engineer. Just consider the ‘cutting edge’ environment that he walked into! Because the Board saw the vital need for wastewater treatment, the State of Massachusetts had become the U.S. leader in the field as early as the 1870’s. By about 1887 this Board of Health had been given the authority for wastewater disposal and they proceeded to establish the first water quality standards in the U.S. and to form the first State Bureau of Sanitary Engineering.[5]

Established in 1887, the Lawrence Experiment Station’s studies on water and wastewater treatment had a “deep and far-reaching” influence on sanitary engineering.[6]

At about the same time (1889-90), the country’s first large wastewater treatment plant, (utilizing chemical precipitation) was built in Worcester, MA. It is easy to imagine how such an environment provided Charles Gilman Hyde with the practical training and experience that would serve him well throughout his career.

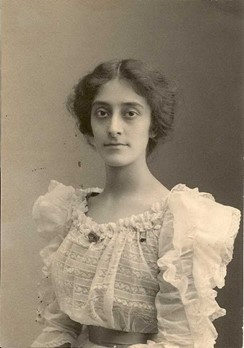

While working at the Massachusetts State Board of Health, Charles Gilman Hyde met, courted and on May 21, 1901 married Margherita Isola in Waban, Newton Massachusetts. After the wedding reception, Charles, suspecting that his good-natured friends ‘might be up to something,’ planned their departure (by horse drawn carriage) to avoid the traditional ‘hazing’ of newly-weds.

However, the driver was slow to depart, allowing a crowd to swoop down and serenade the newlyweds and decorate their carriage with cans, old boots and ribbons. To make matters worse, the driver took the bumpiest route from Waban to their destination in Boston, giving the young couple what must have been the bounciest carriage ride of their lives. When they reached their destination, Charles and Margherita discovered that the “driver” was actually the chief usher of the wedding party in disguise and the slow departure and rough ride had been arranged by their friends to give them a memorable start to their honeymoon![7]

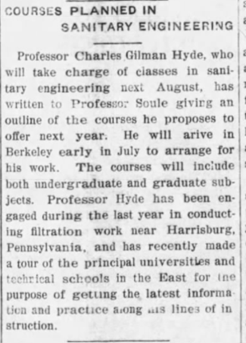

Some four years later Charles, Margherita and their growing family arrived at the University of California at Berkeley, where he was to start an undergraduate and graduate program of courses in Sanitary Engineering. How and why was Hyde able to land a University faculty position some 3,000 miles away from his then current place of employment? Here’s why…

Benjamin Ide Wheeler, the President of the University of California, realized that the study of Sanitary Engineering would become a critically important component of an academic program for addressing the sanitation issues created by urban growth in California. When he started his search for a person who could establish a Sanitary Engineering curriculum at the University, President Wheeler recognized that Massachusetts was a leader in this field [8] and Charles Gilman Hyde came highly recommended to him.[9]

Hyde’s experience at the Massachusetts State Board of Health was part of the reason he was appointed to the position of Assistant Professor of Sanitary Engineering at Berkeley.

Hyde’s experience at the Massachusetts State Board of Health was part of the reason he was appointed to the position of Assistant Professor of Sanitary Engineering at Berkeley.

When Professor Hyde started the UC Sanitary Engineering program, the knowledge and practice of wastewater treatment in California was rudimentary at best. The following observations by Professor Wilfred H. Langelier, Hyde’s colleague at UC Berkeley, gives us a sense of this:

“When Professor Hyde came to California, the most elaborate sewage treatment plant was a septic tank. Nobody knew how it worked – they just knew it worked and was suitable for certain areas, and entirely unsuitable in many places that had brought these in for municipal treatment. It was necessary to do a lot of reading, studying, and experimenting in those early days…Professor Hyde was the first of the sanitary engineers here in the state and I believe I was the first sanitary chemist. We had to work, and Hyde was a worker.”[10]

Because Professor Hyde understood that an effective sanitary engineer needed a good grounding in chemistry and biology—subjects beyond the traditional civil engineering curriculum—he expanded the program accordingly. Sanitary Engineering became an “add-on option” to the undergraduate Civil Engineering major that students could elect to follow.

In addition to the basic requirement of two semesters of freshmen chemistry, students choosing the UC Sanitary Engineering option were required to take three units of quantitative analysis, three units of organic chemistry, three units of general bacteriology, and one unit of aquatic biology. Even though Professor Hyde was able to eliminate some traditional elective civil engineering courses, many students found it necessary to complete an additional year of study to satisfy the Sanitary Engineering option.[11] The additional coursework made the Sanitary Engineering option equivalent to many of the MS programs at other universities.[12]

Professor Hyde’s insistence that chemistry must be part of the Sanitary Engineering curriculum resulted in the recruitment, in 1916, of Professor Wilfred Langelier, a chemist at the Illinois State Water Survey. Together, “Professors Hyde and Langelier became one of the most effective teams in the evolving field of sanitary engineering”.[13]

The involvement of chemists (and later biologists and ecologists), pioneered by Hyde at UC Berkeley, has become “standard practice” in Sanitary (later Environmental) Engineering throughout the US and in other parts of the world.

Professor Hyde served for 39 years at UC Berkeley, except for a 2-year leave of absence to serve as a major in the Sanitary Corps, U.S. Army, during The Great War (1918-19).[14]

During his tenure at Berkeley he served as the Dean of Men for two years (1926-28). On becoming Emeritus in 1949 Professor Hyde was awarded the Honorary Doctor of Laws by UC President Gordon Sproul who stated that “…The West is a fairer, sweeter land because of his concentrated work on its water”.[15]

A truly remarkable aspect of Professor Hyde’s long academic career was his ability to inspire students with a lasting passion for sanitary engineering. He encouraged student participation in his classes, which were more like graduate seminars than undergraduate lectures and included field trips to plants as far away as the Central Valley. A former student recalled that:

“His typical approach was to give out all the class assignments at the beginning of the semester. Then he never talked about them again. His lectures were very interesting but had nothing to do with the subject matter he had assigned. It was up to you to follow the study assignments and do the problems and turn them in on time. Otherwise you flunked!

…I think that was the most important thing I learned from those days at Berkeley – discipline. It came in very handy in later years” Joseph P. Nicoletti.”[16]

His close colleague Professor Langelier recalled how Professor Hyde created a camaraderie with his students:

His close colleague Professor Langelier recalled how Professor Hyde created a camaraderie with his students:

“At his first meeting with the students after they had registered and enrolled, he would have a dinner party at his home. Every year, every fall, he entertained all the new students along with the old students. They played the usual social games, and it gave them a good chance to get acquainted. So, our sanitary engineers were always a well-knit group… Mr. Stead (Frank, Class of 1930) and Mr. Ongerth (Henry, Class of 1935) and Mr. DeMartini (Frank, Class of 1927), all students of Professor Hyde, said that they became a part of the Hyde family circle by the time they were seniors and felt quite gratified to be able to do so.”[17]

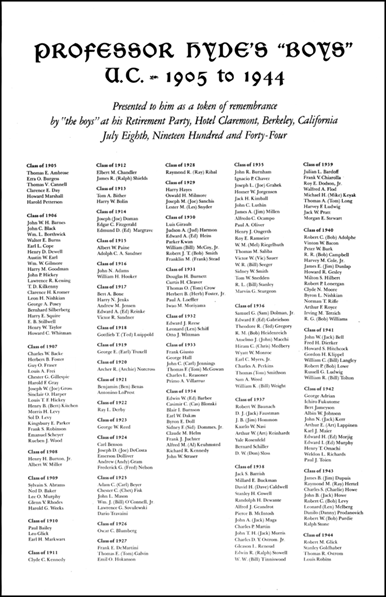

This ‘family circle’ of students became known as ‘Professor Hyde’s Boys’ and, on his retirement in July 1944, he was presented with a personalized document titled “Professor Hyde’s Boys 1905 to 1944 that listed all of his former students by class year. Professor Emeritus David Jenkins noted that the list of names on this document ‘reads like a ‘Who’s Who’ of the California Sanitary Engineering profession. Among it one finds the founders of many of today’s major environmental engineering consulting firms, former CWEA presidents and the leadership of the State of California Health Department Bureau of Sanitary Engineering…’[18]

Professor Hyde’s talents extended far beyond the ‘academy.’ He was a leader in the formation of the California State Department of Public Health Bureau of Sanitary Engineering, the California Sewage Works Association (now the California Water Environment Association, CWEA) and the Federation of Sewage Works Associations (now the Water Environment Federation, WEF).

Starting in 1850 with the Sacramento Outbreak, California experienced problems with typhoid fever outbreaks. From his work at the Massachusetts State Board of Health Professor Hyde was well aware of the linkage between typhoid and wastewater. Indeed, Chester Gillespie recalled that Professor Hyde told him:

“…that most of his work was down in the sewers, studying typhoid fever, so he always carried bananas with him because he didn’t have to peel ‘em till lunchtime.” [19]

In about 1911 Hyde was retained by the California State Board of Health as a sanitary engineer to work on the typhoid problem. Also, at about that time (1915), a colleague of Professor Hyde’s, Professor George Ebright M.D., UC Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine, was made President of the California State Board of Health by Governor Hiram Johnson 1915.[20]

Both he and Hyde were acutely aware of the typhoid problem and together they proposed the formation of a Bureau of Sanitary Engineering within the State Board of Public Health which would have authority over drinking water supplies and oversight of municipal wastewater treatment.[21] Through the efforts of the Ebright-Hyde team and with the support of Governor Hiram Johnson, on May 24, 1915, the State Legislature passed an Act that created a Bureau of Sanitary Engineering within the State Board of Public Health.

The new Bureau started operation in the old UC Civil Engineering Building on August 8, 1915 with Chester Gillespie as its first Director.[22]

This was a ‘cozy’ arrangement for Hyde (Professor) and Gillespie (former student) especially since Professor Hyde continued to be a consultant to the Bureau. Indeed, the influence the University and Professor Hyde on the Bureau lasted for many years beyond its relocation and Professor Hyde’s ‘retirement’ since, for its first 63 years, the Bureau Directors – Chester G. Gillespie (1915 to 1946), Edward Reinke (1946 to 1963), Herb Foster (1963 to 1968) and Henry Ongerth (1968 to 1978) were all ‘Hyde’s Boys’!!

Professor Charles Gilman Hyde and Ed Reinke (Secretary-Treasurer and Past President of the CSWA)

The California Sewage Works Association (CSWA, now the California Water Environment Association, CWEA) was founded in 1928 and, as one might expect, Professor Hyde played a prominent role in its formation; he was one of the first members in 1928 and was one of the first CSWA Directors and one of the first delegates to the Federation of Sewage Works Associations (now the Water Environment Federation, WEF).

He presented papers at every CSWA convention between 1929 and 1939 on topics that included anaerobic digestion, activated sludge and slime growths in sewers. His service to CSWA included chairing the Awards Committee and the Publicity Committee, assisting in the first CSWA operator school, organizing the 1943 CSWA Fresno training conference to which he brought U.S. military staff studying at Berkeley.

Professor Hyde was a member of the ‘Committee of 100’ that was responsible for forming the Federation of Sewage Works Associations in 1928. He was the CSWA representative on the FSWA Board of Control and member of its Executive Committee from 1931 through 1933, and from 1940 through 1942. In 1938, Professor Hyde was given the honor of writing the introductory chapter of ‘Modern Sewage Disposal’ – a book commemorating the FSWA’s 10th anniversary.

‘Who in Hell is Hyde?’ blared a Mr. J.G. Davies of the Sacramento Retail Merchants’ Association Executive Committee in the June 17, 1919 issue of the Sacramento Bee. This was the opening salvo of an attack on Professor Hyde at a meeting concerning the use of Sacramento River water for augmenting the City of Sacramento water supply. Mr. Davis supported the continued use of groundwater wells and saw no need for the expensive construction and operation of a water treatment plant recommended by Professor Hyde. After he concluded Professor Hyde was ‘was only a college teacher.’[23]

Not so, responded the Sacramento Consolidated Chamber of Commerce as they referred Mr. Davies to the impressive list of Professor Hyde’s achievements in ‘Who’s Who in America – and what an impressive list this was! By 1919, at the age of 45, Charles Gilman Hyde had accomplished more than most people do in an entire working career and these achievements were not just limited to academia. He had:

Following the newspaper ‘spat’ Professor Hyde made a presentation to the Sacramento City Commission (the predecessor to the Sacramento City Council) and to a public mass meeting in which he pointed out that groundwater was not a sustainable long-term water supply source and would not support the future growth of the City.

Subsequently Professor Hyde was retained by the City of Sacramento as the chief consulting engineer for the design and construction of Sacramento River Water Treatment Plant.

Over the next 51 years, Professor Hyde’s accomplishments and his contributions to the field of sanitary engineering continued to grow to the point where nearly every major water and wastewater system on the West Coast was influenced by his work.

For example:

Report on the collection and disposal of the sewage for San Diego County, California (with David Caldwell)

In all of these endeavors he became respected for his honesty and forthrightness. Consider the remarks in the following excerpt from the 1941 report (with AM Rawn and Harold Farnsworh Gray-one of the 1907 ‘Hyde’s Boys’) on ‘The collection, treatment and disposal of sewage and industrial wastes of the East Bay Cities…’

‘The East Bay Cities, by reason of the lack of any program of sewage treatment and disposal methods, have rankly abused the extraordinary opportunities available for an economical and effective disposal of sewage or treated effluents by dilution in the waters of San Francisco Bay. Because of this bad practice the shores and shore waters of the East Bay Cities have become obnoxiously and notoriously foul and an affront to civic pride and common decency’

Wouldn’t it be refreshing if today’s engineers would write like this instead of using the manufactured, coddling prose that one often finds in their reports…

In addition to all this, Professor Hyde’s humanitarian and community service were extensive. He was on the executive councils of the Boy Scouts of America, the Berkeley YMCA and the Red Cross for over 20 years… and illustrating the breadth of his character and interests one should note that he was a member of both the Bohemian Club and the First Congregational Church of Berkeley.

‘Only a college teacher’ indeed!

[1]

Brownwood, Robert, California’s Drinking Water Program, California Nevada Section AWWA, Vol. 34, No. 2, (Spring 2020), p. 27.

[2]MIT Yearbook, 1896

[3] Ibid

[4] Chi Epsilon, Civil Engineering Honor Society, National Honor Member Bio Page, Charles Gilman Hyde, https://www.chi-epsilon.org/XEWebGeneral2/About/NHMBio.aspx?MemberId=1.

[5] Chall, M., Chester Gillespie Interview (Oral History), May 18, 1971, p.2.

[6] Metcalf, Leonard and Harrison P. Eddy, American Sewerage Practice, Vol. I, Design of Sewers, McGraw Hill Book Company, Inc., New York and London, 1928, p. 29.

[7]Boston Globe, “Chief Usher Acted as Cabby”, May 24, 1901. p.3.

[8] Chall, M., Chester Gillespie Interview (Oral History), May 18, 1971, p.2.

[9] Ibid

[10] Chall, M., Wilfred Langelier Interview (Oral History), February 22, 1971, p. 21.

[11] Ibid., p. 21.

[12] Ibid, p. 22.

[13] Mendelsohn, I., Public Health Reports, Vol. 39, No. 33 (Aug. 15, 1924), p. 1991.

[14] Pearson, E. A., Introduction to Wilfred Langelier Interview (Oral History), February 22, 1971.

[15] Social Networks and Archival Context, Biography, Charles Gilman Hyde, 2020 https://snaccooperative.org/view/61237128

[16] Chi Epsilon, op. cit.

[17] Scott, Stanley, EERI Oral History Series, Vol. 14, Joseph P. Nicoletti, 2006, EERI, UC Berkeley, pp. 4-5.

[18] Ibid

[19] Jenkins, D., Charles Gilman Hyde Presentation, Academy of Distinguished Environmental Engineering Alumni, 2014.

[20] Chall, Malca, Chester Gillespie Interview (Oral History), May 18, 1971, p.2.

[21] JAMA, Medical News, February 27, 1915, p. 750.

[22] Chall, Gillespie, p. 3.

[23] Ibid, p. 28.

[24] Sacramento Bee, June 18, 1919, p. 6.

[25] Social Networks and Archival Context, op. cit.